Phylotrackpy

Introduction

Digital/computational/in silico evolution is a powerful technique for better understanding the process of evolution. One of the major benefits of doing in silico evolution experiments (instead of or in addition to laboratory or field experiments) is that they allow perfect measurement of quantities that can only be inferred in nature. Once such property is the precise phylogeny (i.e. ancestry tree) of the population.

At face value, measuring a phylogeny in in silico evolution may seem very straightforward: you just need to keep track of what gives birth to what. However, multiple aspects turn out to be non-trivial (see below). The goal of Phylotrackpy is to implement these things the right way once so that we all can stop needing to re-implement them over and over. Phylotrackpy is a python library designed to flexibly handle all aspects of recording phylogenies in in silico evolution.

Note: this library is essentially a wrapper around the Empirical Systematics Manager, which is implemented in C++. If you need a C++ phylogeny tracker, you can use that one directly (it is part of the larger Empirical library, which is header-only so you can just include the parts you want).

Features

Flexible taxon definitions

One of the central decisions when creating a phylogeny is choosing what the taxonomic units (i.e. the nodes in the tree) are. In a traditional phylogeny, these nodes are species. However, the concept of species is so murky that it is impossible to generically apply to computational evolution systems (we’d argue that it’s questionable whether it could even be applied to biological data recorded at perfect temporal resolution, but that’s a separate conversation). One alternative would be to make a phylogeny in which all nodes are individuals, but these trees are usually so large that they are impractical to work with.

Increasingly, biologists have embraced the idea of building trees in which the taxonomic units are not species. Often, these are denoted by referring to them as an “X tree”, where X is the taxonomic unit of interest. A traditional phylogeny, then, is a species tree. This terminology is particularly common in cancer evolution research, in which species trees are often contrasted with “clone trees” or “gene trees”, in which the taxonomic units are genotypes.

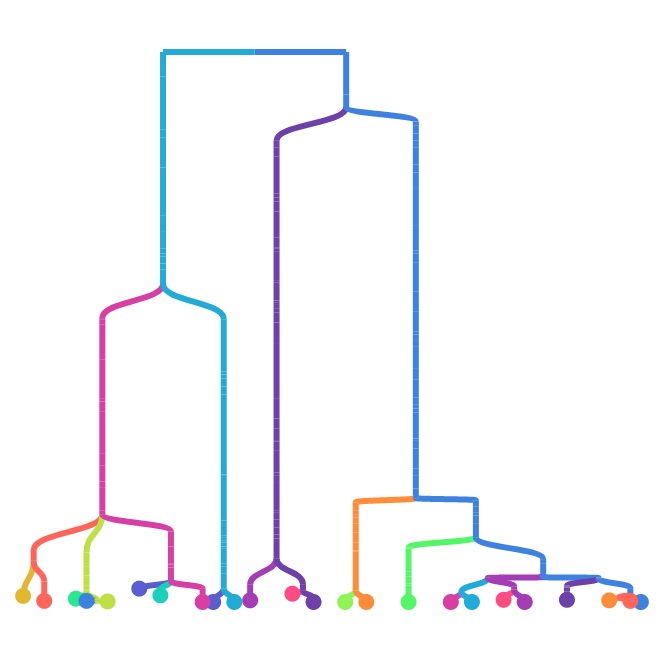

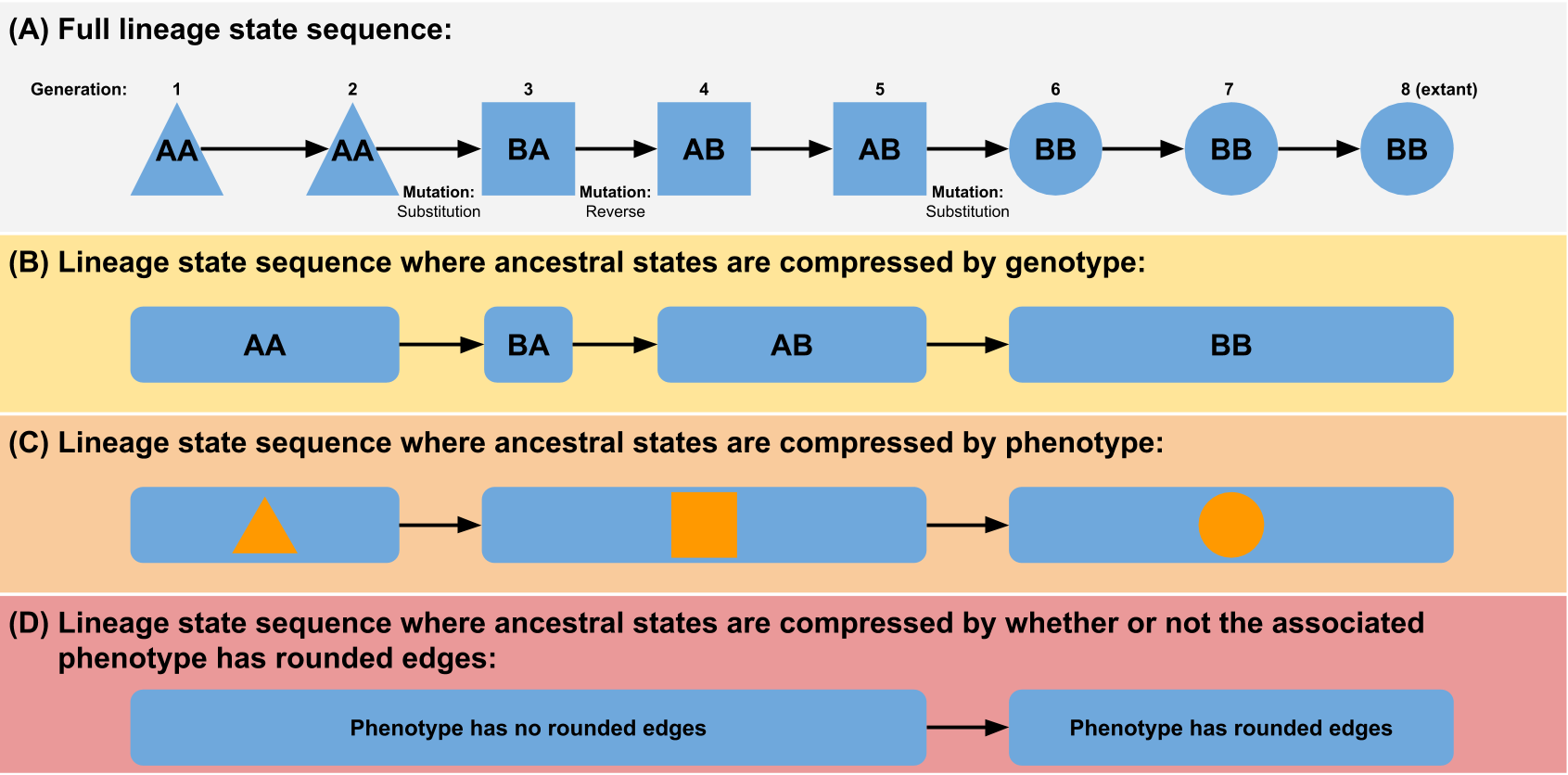

We can generalize this concept - any phylogeny of individuals can be abstracted by lumping individuals together based on a shared feature (see figure). This feature could be something simple like a phenotypic or genotypic trait, or it could be something more complex. For example, to approximate something more like a traditional biological species concept, you could choose to define an individual as being a member of a new taxonomic unit if it fails to produce successful offspring when recombined with an individual prototypical of its parent species (although note that the stochasticity inherent in this definition could have some unexpected side effects). The broader the grouping, the smaller the phylogeny will be (e.g. a genotype tree will be larger than a phenotype tree).

(Figure from “Quantifying the tape of life: Ancestry-based metrics provide insights and intuition about evolutionary dynamics” published in the proceedings of ALIFE 2018)

(Figure from “Quantifying the tape of life: Ancestry-based metrics provide insights and intuition about evolutionary dynamics” published in the proceedings of ALIFE 2018)

So how does Phylotrackpy handle this problem? By giving you the power to define taxonomic groupings however you want! When you construct a Phylotrackpy Systematics object, you give it a function that it can use to determine the taxonomic unit of an organism. Later, when organisms are born, you will pass them to the Systematics object and it will run that function on them. If the result matches the result of calling that function on the new organism’s parent, then the organism will be considered to be part of the same taxonomic unit (Taxon) as its parent. If the results do not match, the new organism will be considered to be the start of a new taxon descended from the parent’s taxon.

Note that multiple taxa may evolve that are the “same” (i.e. running the function on organisms in each yields the same result); each unique evolutionary origin will be counted as a distinct taxon. For example, let’s imagine we are building a phylogeny of real animals in nature and grouping them into taxa based on whether they spend more than 50% of their lives in water. Fish and whales would be parts of two different taxa. Even though they both live their whole lives in the water, there would be a “land” taxon in between them on the line of descent.

Example:

from phylotrackpy import systematics

# Assuming that the objects being used as organisms have a member variable called genotype that stores their genotype,

# this will created a phylogeny based on genotypes

syst = systematics.Systematics(lambda org: org.genotype)

Pruning

Phylogenies can get very large. So large that they can cause you program to exceed its available memory. To combat this problem, phylogenies can be “pruned” so they only contain extant (i.e. not extinct) taxa and their ancestors. If the store_outside variable for a systematics object is set to False (the default), this pruning will happen automatically. If you truly want to keep track of every taxon that ever existed, you can do so by setting store_outside to True. If you want to keep track of some historical data but can’t afford the memory overhead of storing every taxon that ever existed, an intermediate options is to periodically print “snapshot” files containing all taxa currently in the phylogeny.

Phylostatistics calculations

Phylogenies are very information-dense data structures, but it can sometimes be hard to know how to usefully compare them. A variety of phylogenetic summary statistics (mostly based on topology) have been developed for the purpose of usefully making high-level comparisons. Phylotrackpy has many of these statistics built-in and can automatically output them. It can even keep running data (mean, variance, maximum, and minimum) on each statistic over time in a highly efficient format.

Available statistics include:

Mean/max/min/sum/variance pairwise distance

Colless-like index (a variant of the Colless index adjusted for trees with multifurcations

Sackin index

Phylogenetic diversity

Efficiency

Tracking phylogenies can be computationally expensive. We have sought to keep the computational overhead as low as possible by implementing Phylotrackpy in C++ under the hood, and in general writing the code with an eye towards efficiency.

We also provide the option to remove all taxa that died before a certain time point (the remove_before method). Use this with caution, as it will inhibit the use of many phylogenetic topology metrics. In extreme cases it may be necessary, though.

If you need substantially higher efficiency (in terms of time or memory) or are working in a distributed computing environment (where having a centralized phylogeny tracker can pose a large bottleneck), check out the hstrat library, which lets you sacrifice some precision to achieve lower computational overhead.

Flexible output options

At any time, you can tell Phylotrackpy to print out the full contents of its current phylogeny in a “snapshot” file. These files will be formatted according to the Artificial Life Phylogeny Data Standard format. By default they will contain the following columns for each taxon: 1) unique ID, 2) ancestor list, 3) origin time, and 4) destruction time. However, you can add additional columns with the add_snapshot_fun method.

You can also print information on a single lineage.